GNEP will also help reduce the risk of weapons materials proliferation, according to Dr. Kathryn McCarthy, INL’s director of Advanced Nuclear Energy Systems Integration. “(Former President) Jimmy Carter stopped reprocessing back in the ‘70s, because (he thought) people will follow our example and they will stop, too,” which McCarthy reminds hasn’t really happened.

“There are (still) countries that are recycling using processes that are against U.S. policy,” she explains. “Iran is enriching uranium. If you’re going to build a weapon, the easiest way is to enrich uranium.”

GNEP is designed to avoid this scenario by providing a secure recycling network within the cooperating countries. By employing fast breeder reactors, nuclear-capable countries within the GNEP alliance can act as reprocessing centers, supplying fresh LWR fuel in return for waste, then reusing that waste to generate power and make more fuel.

Essentially, non-nuclear and developing countries could construct Gen II-type LWR power plants, using fuel supplied by the GNEP countries. These LWR plants could be turn-key operations, which the consumer nations could run without being concerned about nuclear waste issues. Under GNEP, any new fuel would be traded for the spent fuel, which would be reprocessed in GNEP countries for use in Gen IV reactors. In the GNEP scenario, the fuel cycle is global and much more complete and efficient -- reducing waste and extending the useful energy content of all nuclear fuels.

“What we want to do is look at ways of removing the incentive to enrich for energy purposes,” says McCarthy, adding that it will take years to build and test a recycling model for the future. “We need to prepare for that now, because this is a relatively lengthy process. Twenty years to demonstrate and 10 to 20 years in terms of starting to deploy the facilities that we will need,” she adds.

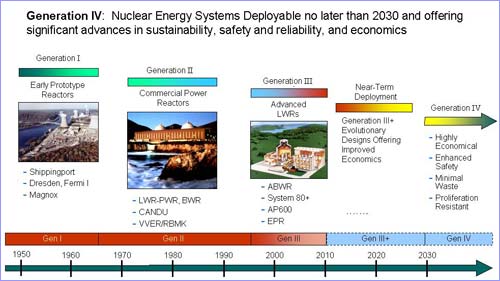

While Gen IV reactors hold the hope for improved efficiency, safety and security, it is generally recognized that the commercial applications will not appear until 2030.

Recycling versus Storage

In the 40-plus years since the first U.S. nuclear plants began generating power, all of the spent fuel -- what is generically termed waste -- would easily fit on a football field just five feet high. Weighing 48,000 metric tons, this represents a great deal of waste material, but considering that 20 percent of the United States’ electrical power is generated from nuclear power, this amount is at the same time surprising small.

Regardless, it is generally understood that recycling current and future LWR spent fuel is preferable to entombing it in repositories like Yucca Mountain. In fact, most all this so-called waste still has significant energy potential, however it cannot be utilized by current LWR power plants.

Most nuclear “waste” is still usable, but not by current Gen II light-water reactors. The GNEP scenario will make the best use of this spent fuel.

“More than 95 percent of what went in hasn’t changed at all,” says McCarthy of typical LWR fuel. “The rest of it -- less than five-percent -- is primarily stable fission products -- -- they don’t decay -- and a very small amount of them are radioactive.”

According to industry experts, the U.S. is suffering from an incomplete nuclear fuel cycle. The GNEP plan would allow for much more efficient use of nuclear fuel and vastly extend the useful life of repositories like Yucca Mountain. For example, under a GNEP scenario, instead of needing to store entire football field of nuclear waste, the actual amount would easily fit into the end zone. This makes a great deal of sense according to McCarthy, especially considering the political realities highlighted by Yucca Mountain.

“There’s been a lot of effort put into Yucca Mountain” says McCarthy, adding, “We want to make one repository work. Basically the goal is for the rest of this century, even with the increase in the deployment of nuclear reactors.”

“If you look at the big picture and how valuable it is not having a second repository, it’s pretty darn valuable because the next repository has to be located east of the Mississippi,” says McCarthy laughingly, “Well, good luck. We’re having a hard enough time in Nevada.”

Entire contents © 2006 Corland Publishing. Use of editorial content without permission is strictly prohibited.

All Rights Reserved. Privacy Policy Legal Contact Us. Site developed by ICON.